Link to Acropolis Plan

(Opens in a new window)

The acropolis still dominates the Athens skyline, and seems to rise above the human realm. The acropolis was an important site as early as the Bronze Age, when it housed a Mycenaean citadel. In the 6th century BCE, the Athenian tyrants would use the acropolis as a base, but they were the last of the ancients to live there. By the time of the Classical Age, the acropolis was home to the gods--not mortals. Further, the burning of the acropolis during the second Persian invasion (480 BCE) left the site almost barren. It would not be until after the middle of the 5th century BCE, at Athens's material and cultural height, that reconstruction of the acropolis would occur.

The rebuilding of the acropolis was urged by Pericles, to express the power and glory of Athens, the city that was teacher of the Greeks and head of the Delian League that continued the fight against barbarian Persia. These messages can still be seen in the architectural and sculptural remains of the acropolis. Buildings played religious and civic roles, with the Parthenon itself as both a repository for the treasury of the Delian League and a primary site of the Panathenaic Festival, held every 4 years in honor of Athena, the patron of the city.

The Panathenaic Way marked the route of the procession for this festival. The road began at the Dipylon Gate, worked its way through the agora, and finally rose to the Propylaea, the entryway to the acropolis:

Visible to the right of the entryway is the small Ionic temple to Athena Nike (victory), built early in the Peloponnesian War (427 BCE), shortly after the death of Pericles. Its sculptures included depictions of battles between Greeks and Persians:

The Propylaea, begun in 437 BCE, shortly before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, includes elements of both the Ionic and Doric architectural orders. A number of Doric structures utilize some Ionic elements--the continuous interior frieze on the Parthenon represents one Ionic element in the quintessential Doric temple. But it is extremely unusual to see Doric and Ionic columns together in a row, as in the Propylaea. Doric columns are evident from the outside; here the view is looking back from the inside of the acropolis:

Within the Propylaea, one can still see columns from both orders; here the two inner columns have a typical Ionic base, while the outer column, resting directly on the floor, implies the Doric order.

This design may express that Athens encompassed both elements of the Greek world. Perhaps as a result of this hubristic attitude, the Athenians were never able to complete the building--the war drained Athens' resources. Note, on the lefthand side of this view, the "bumps" on the wall:

These are "bosses." Used in the transportation of marble blocks, they would have been removed in the final stages of construction.

After one walks through the Propylaea, the two main structures remaining within the acropolis come into view: the Erechtheon ahead to the left and the Parthenon ahead to the right. During the Classical Age, a number of other structures would have been visible, but these two would still have dominated the area.

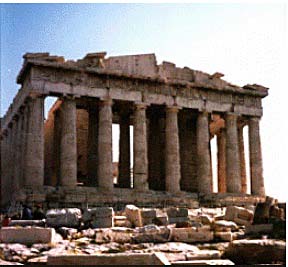

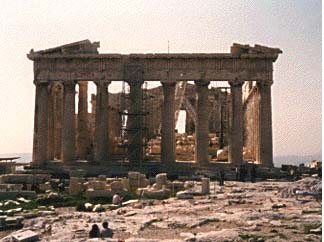

The Parthenon, as a masterpiece of Doric architecture, exudes the strength appropriate to a city that was preeminent in the Greek world at the time. The temple and its sculpture took 15 years to build; it was completed in 432 BCE--just before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. The end immediately visible is actually the back:

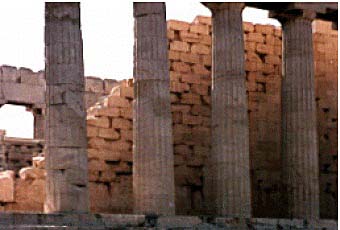

The Panathenaic Procession would make its way along the side of the Parthenon. In the first picture below, the wall of the cella, the inner structure that would have housed Phideas's famous chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of the goddess, is visible behind the columns. The second view highlights part of the entablature, above the outer columns on the north side.

to the ceremonial entrance, where a new peplos (a robe) would be offered to the goddess:

Phidias' statue, surrounded by a pool of water to keep the ivory from cracking, would have occupied the cella room accessible from this side of the Parthenon. But the cella was divided; a second room, accessible from the back--the side immediately visible on entering the acropolis--would have held records and the treasury of the Delian League. It was this second room that was often considered the home of the goddess.

Much of the surviving sculpture from the Parthenon is now in the British Museum, having been purchased by Lord Elgin from the Turkish rulers of Greece early in the 19th Century. While the subject of the frieze has recently sparked debate, the metopes' sculpture sounded the common Greek theme of civilization struggling against barbarism. Pictured below are samples from the British Museum, depicting the battle between the Lapiths and the centaurs. The centaurs, half horse and half human, were unable to control themselves at a Lapith wedding, and thus sparked a violent battle with their hosts.

Across from the Parthenon lies the Erechtheon. In the open space between them is the site of an earlier temple to Athena which was destroyed when the Persians burned the acropolis. The site was left undeveloped as a reminder of Persian sacrilege.

Some of the materials left after the Persian sack were reused; column drums, for example, were included in later construction of the Acroplois walls.

Before the remains of the archaic temple, directly ahead as one passed through the Propylaea, would have stood a huge statue of Athena. Over 20 feet tall, this statue would have been visible to sailors rounding Cape Sounion on their way back to Athens. Dedicated after the victory over the Persians, the statue presented Athena holding a spear and a shield, on which was depicted the battle with the centaurs--yet another representation of the struggle between civilization and barbarism. All that remains of the statue are traces of the pedestal.

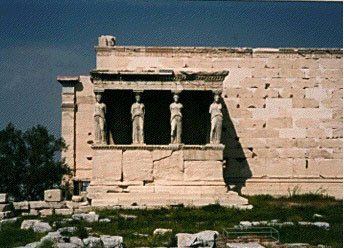

Immediately visible on the Erechtheon is one of the most intriguing features of the Athenian acropolis, the porch of the karyatids, columns carved in the shape of women. The purpose of this porch remains a mystery, though since it is the one element of the Erechtheon that encroaches on the site of the old temple, it may express a link to the past.

Karyatids were employed in buildings of the Ionic order, and other elements of the Erechtheon confirm that. Note below the slender, elegant columns, with their distinctive scroll capitols.

The tree reminds us of a sacred spot encompassed by the Erechtheon. The competition between Athena and Poseidon, to determine who would be the patron of the city, took place here. On one version of the story, Poseidon offered the people of Athens a salt water spring; Athena offered the olive tree. It was Athena, after all, who represented wisdom!

The Erechtheon was the last of the major acropolis structures to have been built. It was begun during the Peace of Nikias in the Peloponnesian War but was not completed until 408 BCE--roughly five years before Athens's defeat. While the Parthenon played largely a civic role, in festivals and as a treasury for Athens' Delian League, the Erechtheon had greater religious significance. It had to be built on several levels to accommodate the sloping terrain and because it was designed to enclose a number of sacred sites. In addition to the contest between Athena and Poseidon, for example, the site is associated with the tomb of Erechtheus, the legendary first king of Athens. Erechtheus was associated with both Athena and Poseidon, and the Erechtheon seems to be a double temple, dedicated to both gods.

The north (lower) porch--to the left in the photo below--encompassed an altar to Poseidon. This porch led to a west room in the Erechtheon that supposedly marked the site where Poseidon opened the salt water spring. On the east side--the far end on the right in the photo below--stood the porch that led into Athena's area.

This view, from the east side, shows the columned face of Athen's sanctuary. The second picture below looks through the east porch into the cella of Athena and on to the west end:

The Erechtheon housed the old wooden cult statue of Athena. Though less magnificent than Phidias's gold and ivory statue in the Parthenon, the early statue was considered more sacred.

Moving to the northeast corner of the Erechtheon, we can see the porch before Poseidon's part of the building.

The view directly from the north shows the entry from the porch to the west room that supposedly marked the site where Poseidon opened the salt water spring.

The remains on the acropolis provide a glimpse of the artistic accomplishments of Athens at its height. The architectural designs express in material form the rational ideals that made Athens a teacher to the world. But there were other sides to the Athenian outlook. As Thucydides reports, during the second half of the 5th century BCE, the period of the reconstruction of the acropolis, Athenians could be as ruthless as any of the "barbarian" peoples they so often compared themselves to. Thus, at the end of the century, the Spartans could claim, as the Athenians did during the struggle against Persia at the start of the century, to be fighting for the freedom of Greeks. Sparta's victory, in 403 BCE, marked the end of Athens's political pre-eminence, though the city's cultural contributions, e.g., in the 4th century BCE philosophical work of Plato and Aristotle, continued.

--------------------

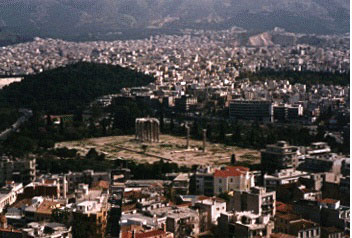

From the acropolis other sites of Classical Athens are visible. Most important is the agora, the meeting place and market that became the heart of democratic Athens. Also visible here is the Hephaesteon, one of the best preserved temples in Greece. It, like many other temples, including the Parthenon, was converted for use as a Christian church.

On the south slope of the acropolis lie the remains of the theater of Dionysus, where the plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles were performed. The theater was expanded and redesigned many times; what is visible dates from the Roman, not the Classical era.

Also visible are the remains of the temple to Olympian Zeus. Construction on such a temple was begun in the 6th century BCE, during the tyranny (prior to the emergence of Athens' democratic institutions). Never completed then, it was redesigned and restarted at various times into the Roman era--but still was never finished.

The acropolis also offers vistas of the modern city. Here, the traditional tile roofed houses close to the acropolis give way to contemporary concrete apartments.