ATHENIAN AGORA

of the Classical

ATHENIAN AGORA

The agora, literally, the marketplace, was more like a meeting place for Athenians. When the acropolis became home to the gods rather than kings or tyrants, the policial and social heart of the city moved down from the hill to the plain of the agora. This, too, housed a sacred precinct, a temenos marked by boundary stones and bordered by civic, economic, and religious buildings.

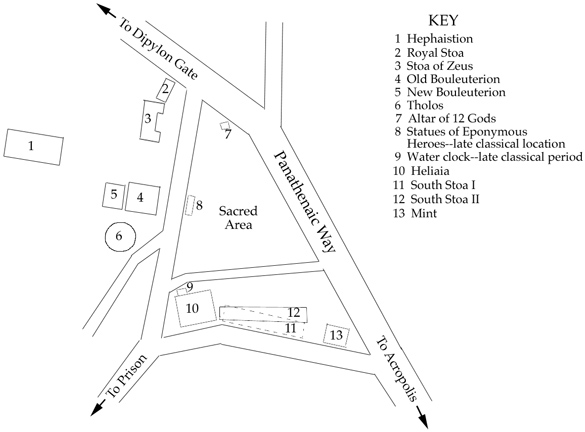

ROUGH PLAN OF AGORA WITH MAJOR CLASSICAL STRUCTURES MARKED

During the Classical Age, the sacred area itself (roughly the central triangle above) was largely empty, home to altars and other small religious structures and sometimes used as a race course.

IGNORING WHAT CAME LATER

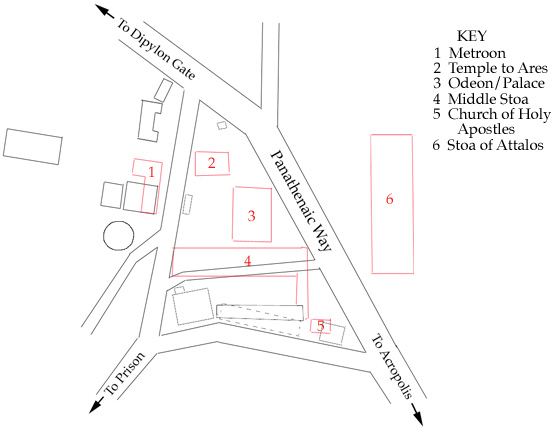

The site today presents a bewildering mix of remains from the Archaic through the Byzantine ages, from ancient Greece through the Christian era. During the Hellenistic and Roman Ages, however, a number of large structures were constructed within the sacred precinct. These remains, along with the reconstructed, Roman Age Stoa of Attalos, now dominate the site. Thus, to imagine the agora at the time of Pericles and Socrates requires that we ignore much of what is visible.

ROUGH PLAN OF AGORA WITH SOME LATER STRUCTURES MARKED

Perhaps the most obvious later addition is the little Church of the Holy Apostles, dating from around 1000 AD:

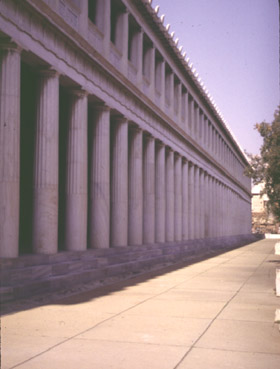

The Stoa of Attalos, on the east side, a gift of a 2nd century BCE Pergaman king who had studied at Athens, has been reconstructed by the American School of Classical Studies and now houses the museum.

Within the sacred area are the remains of the odeon and palace of Agrippa, first constructed in the 1st century BCE, rebuilt and expanded through the 5th century AD:

To the south lies the middle stoa, built in the 2nd century BCE:

THE CLASSICAL AGORA

Link to Rough plan of the Classical Agora

(Opens in a separate window)

None of the buildings pictured above would have existed during the Classical Age. Instead the visitor would have found in the sacred area relatively modest yet important structures such as the altar to the 12 gods and the statues of the eponymous heroes. The eponymous heroes were the people who gave their names to the ten new "tribes" of Athenian citizens, organized as part of Cleisthenes' democratic reforms at the end of the 6th century BCE. At the statue base announcements and notices would have been posted, thus this was an important meeting place in central Athens. The base shown below, though still in the sacred area, is probably a bit removed from the original location early in the classical age.

Thus the sacred area would largely have been open space, used in early periods as a race course and orchestra. The clutter of remains in this area today mark additions largely from the Hellenistic and Roman eras.

Traversing the agora was the Sacred Way, the path of the Panathenaic Procession honoring Athena. This procession, starting at the Dipylon Gate in the city walls, would have passed through the agora just before it made its way up the acropolis to the Parthenon, where the old, sacred statute to Athena would have been offered a new robe, or peplos. This view looks toward the acropolis.

The sacred area of the agora would have been marked not by a wall but by boundary stones, such as the one shown below:

Such boundary markings were essential to maintain the traditional restrictions associated with sacred precincts: It was forbidden to give birth or die within a sacred area. Indeed women and children were not allowed to enter at all. Thus Socrates, whose followers included many young men, would have held his discussions just outside the sacred area.

Indeed, much of public, daily life at Athens occurred in the buildings that bordered the sacred area proper. To the west would have been a number of government buildings associated with the Athenian democracy. To the south would have been economic buildings as well as a court and, further away, the prison complex.

The south side of the classical agora would have been dominated by a stoa, the most visible remains, aptly named the South Stoa II, are from the late classical period. An early building, not surprisingly called South Stoa I, occupied roughly the same area.

To the east of the South Stoa II was probably the Heliaia, a court building. The water clock in front and pictured below date from the end of the classical period.

The state prison was located further south; pictured below are two philosophers by what may have been Socrates' prison cell.

The west side of the agora housed a number of public buildings. At the southwest corner lies the tholos, the circular building that probably served as the office of the Prytaneis, the group of 50 council members who were always available for public business.

THOLOS FROM SE:

THOLOS FROM HILL TO WEST:

Beyond the tholos were the council chambers (bouleuterion). The Council (Boule) of 500, 50 members selected at random from each tribe, prepared business for the assembly to discuss. The Council could not make policy decisions; that role was left to the assembly, composed of all adult male citizens. Each tribes representatives on the Council served as the Prytane for 1/10 of the year. Below is a view of the entrance to the Council chamber.

The council building itself underwent significant changes over the years; a new chamber was built behind the old and is pictured below.

The Assembly (Ekklesia) would have met on the Pnyx hill, located south of the agora and west of the acropolis--shown below from the acropolis.

Further north along the west side of the agora, the Stoa of Zeus was a popular meeting place--for Socrates and many others:

At the north end of the agora, near the panathenaic way, is the Royal Stoa. According to Plato, Socrates, when responding to the charges brought against him, met Euthyphro here and engaged in a discussion of the nature of piety. The remains of the Royal Stoa now lie by the subway tracks. The second view below provides a sense of the difference in ground level between the classical age and 21st century Athens.

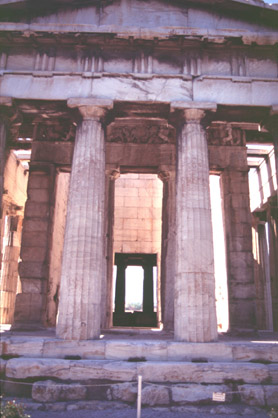

Behind buildings on west side, up the hill, lies the Hephaistion, one of the best preserved Doric temples in Greece.

The Hephaistion, like other temples, was converted for use as a church during the Christian era. Buildings and sacred areas lived on, often, as in the case of the agora, making it difficult to envision the site in its classical age form.

__________________________

For a detailed tour of the agora and its remains, see The Athenian Agora: A Guide to the Excavation and the Museum (American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1990.) The plans used here have been adapted from this volume.