Link to Plan of Delphi and the Surrounding Area

(Opens in a new window)

As the Aegean area was emerging from the Dark Age, two sites served to forge the cultural unity of the Greek world: Zeus's Olympia and Apollo's Delphi. While the Olympic games, highlighting civilized competition among Greeks, may claim precedence, the oracle at Delphi provided an essential meeting place for the exchange of information and ideas. In this, Delphi became associated with Greek moral and intellectual ideals, as evidenced by the mottos on Apollo's temple there: 'Know Thyself' and 'Everything In Moderation'. Apollo's transition from the arrow-hurling, angry deity of the Iliad to the spokesman for self-knowledge and moderation speaks poignantly of the classical Greek legacy.

Delphi was considered the center of the universe, which was represented by the omphalos, the navel. A later sculptural depiction of the omphalos is displayed in the Delphi Museum.

Apollo lived at Delphi for nine months of the year. During that time, he "spoke" through oracles to suppliants from throughout the Greek world--and beyond. Apollo's sanctuary was built onto a hillside, with a spectacular view down to the gulf of Itea, the arrival point for many visitors.

The traveler journeyed up to the Altis (the sacred area,) but there would often be a long wait before the last climb, within the sacred area, to Apollo's temple. One had to appeal to the priests governing the site to make a request of Apollo. Then, before entering Apollo's sanctuary, one cleansed at the sacred spring.

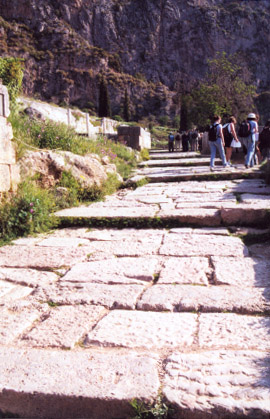

The entrance to the Altis, at the lower end of the sanctuary, marks the start of the sacred way, a switchback path that leads up to the temple.

Grateful cities made dedications, many of which lined the sacred way. Though little is left on the site, museum houses some spectacular artifacts. Just inside the entryway would have been numerous monuments, including a Spartan monument for the victory at Aegospotamoi--the battle that ended the Peloponnesian War. This monument perhaps overshadowed a nearby Athenian offering for the victory at Marathon. Farther up the path are the remains of numerous treasuries, small structures with columned facades, used to house the offerings of cities.

Ahead to the right is the Sikyonian Treasury, a Doric structure in the mid-6th century BCE.

Just beyond the Sikyonian Treasury, near the switchback, is the Siphnian Treasury, an Ionic building from around 525 BCE. The columns before the entrance were karyatids, sculpted female figures. Remains from the pediments and the frieze are visible in the museum.

Above the switchback lies the reconstructed Athenian Treasury, probably dating from the early 5th century BCE.

The reconstruction process was made easier because the Athenians, as usual, carved inscriptions on the stones, thus allowing their accurate placement.

Apollo was not the first to provide oracles at Delphi. Perhaps the earliest was an earth goddess whose oracle was associated with this rock below Apollo's temple.

Just below the temple lies the base for the Naxian sphinx, dedicated around the mid-6th century BCE.

Continuing up the Sacred Way, additional treasuries, including one for Corinth, would have been visible.

Approaching the temple, one passes the Stoa of the Athenians (dating from near the mid-5th century BCE), built against the retaining wall that supported the temple. Here, too, the Athenians carved many inscriptions, this time on the back of the stoa.

Other dedications of note, visible in the museum, include the charioteer (from the tyrant of Gela, about 475 BCE) and the statues of Cleobis and Biton (from Argos in the early 6th century BCE.)

Finally, one arrives at the temple. Here, the stone altar to Apollo, where offerings were made, appears before the entrance to the temple:

The temple would have been an imposing site, with its massive Doric columns. Those that remain still exude the strength appropriate to a deity of Apollo's stature:

As usual, the temple would have had a spectacular view of the surrounding area.

This is actually the third temple on the site; the first was built in the 7th century BCE. The visible remains date from the middle of the 4th century BCE.

How Apollo "spoke" is still uncertain. The traditional account has a priestess (pythia) speak in a trance; a priest would then translate the god's message. Of course, the translation would still require interpretation--the ability to reason beyond the obvious was essential. Recall Herodotus's account of Croesus's failure to consider the ambiguity of Apollo's claim that if Croesus attacked, a great empire would fall.

Despite the prominence of Apollo's temple, there is more to the site. Additional monuments and treasuries were evident before and above the temple.

In addition, Delphi held theatrical and athletic competitions. Immediately above the temple lies the theater; it too had a gorgeous view of the sanctuary and the countryside.

Above the sacred area lies the stadium.

The stone seats for spectators are a later, Roman addition. Greek stadiums (including the one at Olympia) generally provided merely a sloping, grassy area for those viewing the events.

Delphi highlights the unifying force of Greek religious practices. Here, Apollo spoke to all Greeks--and in a way that required the use of those analytic reasoning skills that characterized one aspect of the Greek ideal. The site combined other aspects of the ideal as well, in its glorification of athletic and performing arts. Here, too, the unifying force of Greek religion is present, for such events were linked to celebrations honoring the gods. Apollo may have imparted his wisdom here, but he also provided the impetus for Greeks to express their own wisdom.