Link to Knossos Plan

(Opens in a new window)

The palace of King Minos was rich in mythological lore. Minos himself was believed to be the son of Zeus--the result of one of Zeus's many affairs with mortal women. Minos's palace and the legends associated with it befit the son of a god. Here Daedelus built a contraption so that Minos's wife, Pasiphae, could satisfy her passion for a bull. The union resulted in the Minotaur-half bull, half-man. For his efforts, Daedalus was imprisoned by Minos. Daedalus's invention of wax wings allowed him and his son, Icarus, to fly to freedom--the rest needs no retelling. It was at Minos's palace that Theseus, the Athenian hero, slew the Minotaur and thus released Athens from the yearly tribute of 7 youths and 7 maidens for the Minotaur's consumption. The Minotaur was housed in a labyrinth, a maze from which Theseus emerged only with the help of Minos's daughter, Ariadne, whom he promptly deserted on the way back to Athens. The Greeks were quite sanguine about their heroes. As the Athenian ships returned home, Theseus forgot to give the signal for success. In despair, his father, King Aegeus, threw himself into the sea that still bears his name.

Later Greeks credited Minos with building the first navy and clearing the Aegean of pirates. In contrast to his demand for yearly human tribute, he is also revered as a great lawgiver. (The demand for human tribute also contrasts with the archaeological evidence, which suggests that human sacrifice was extremely rare.) Minos's control of the seas enabled him to build an empire that extended beyond Crete to the Cycladies. There is archaeological evidence for this, as Acrotiri, on the southern Cycladic island of Thera, seems to be a Minoan city.

On Crete, the remains of the palace at Knossos, dating from the 17th century BCE (the second palace period on Crete), justify the mythological depiction of a labyrinth. Constructed in stages over various times, the palace was a huge, multi-storeyed, rambling structure that can still confound visitors. Only some of the major areas and functions can be outlined here; the richness of the site must be experienced firsthand.

Knossos was excavated by Arthur Evans (whose bust greets the visitor at the entrance to the site.) Evans's efforts at reconstruction, however, continue to spark scholarly debate.

One enters Knossos from the west, past 3 underground silos whose exact use remains uncertain.

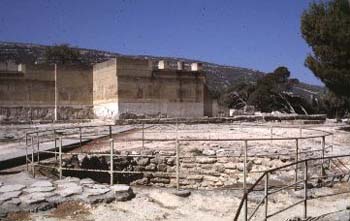

The silos are near the west court, likely a ceremonial gathering place before the palace, as is indicated by the paving and the altar bases as well as the fine construction of the west facade (reconstructed above the ground course in the pictures below.)

At the southwest corner, processional halls, lined with frescoes, wound their way into the palace. On the ground floor, the corridors would lead to a number of ceremonial areas, including the large central court, the dominant feature of all Minoan palaces:

This open area took advantage of the southern Aegean climate and highlighted the Minoan emphasis on nature, evident in frecoes as well as architecture.

Other sections of the site can be described with reference from the central court. Looking back south, one can see (center-left) the reconstructed stylized bull's horns, called by Evans "horns of consecration"--perhaps mirroring the double-peak of Mt Jukus, visible in the distance. Mt Juktos was a sacred area, housing an important peak sanctuary. The second picture below provides a view of the horns from outside the palace, to the south.

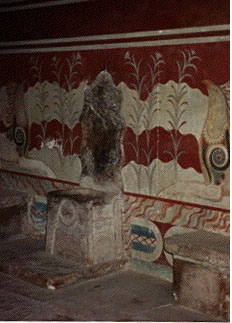

On the west side of the court are a number of important ceremonial and shrine areas. At the north end of the west court lies the throne room. The images below show the view from the central court, the ante room, and finally the throne room itself.

The throne itself may be a later addition--from the period of Mycenaean influence. Moreover, the chair hardly fits the immage of a throne; we must be careful in reading too much into the modern names given various parts of the palace.

Moving south along the west side of the court, romms that have been labeled crypts, storage areas, and the tripartite shrine.

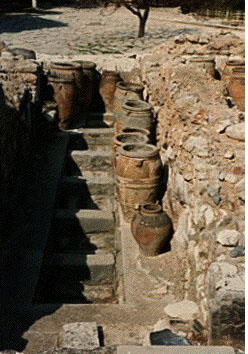

Behind these rooms, on the west side of the palace, are magazines or storerooms, emphasizing the economic function of the complex.

A second storey is also evident on the west side of the palace. One stairway led off the central court.

A frescoed entryway (Propylaeum) to the second storey was accessible from the southwest processional corridors.

The entryway led to a grand stairway, which rose to halls and additional shrine rooms.

Returning to the central court, we can explore the east side of the palace. Here, the land slopes downward. The "royal apartments" are under the palace reconstruction visible here:

The view of the east remains from the central court gives an idea of the enormity of the immensity of the palace.

As we enter the east wing, there are more storage areas to the north.

Looking south, the area Evans thought of as the domestic quarters comes into view.

Evident here are a number of halls and frescoes. Others, disputing Evans, have argued that these were more public halls. Note the stoa-like arrangement in the top two photos; the lower views look through the "King's apartment" and the shrine of the double axes.

Here is a part of the restored dolphin fresco in the "Queen's Hall":

The southeast section of the palace includes anther lustral basin.

Moving through the central court once again, we can visit the north entrance of the palace.

Here too is evidence of a large sculpture of the Minoan bull's horn.

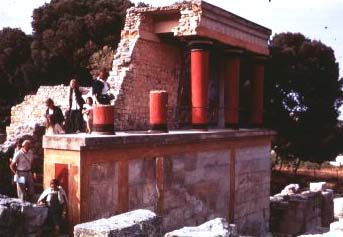

Evans's reconstruction of part of the north entranceway shows typical Minoan columns, which originally would have been made of wood:

A highlight of the northwest area, near the entrance, is the reconstructed "lustral basin." The function of these "basins" remains a mystery. Evans originally felt the stairs led down to a ceremonial cleansing area, but the archaeological evidence for this is not conclusive, in part because there seems to be no drain in the floor.

And there is much evidence for both drainage and water collection systems at the palace.

Outside the palace on the north side is the theatral area, probably used for ceremonial purposes. Leading from here to the west is the oldest road in Europe.

Noticeably missing from Knossos are defensive walls. Though the palace walls themselves were massive, these would not have provided protection against assault. The Minoans seemed secure in their island base, confident that their navy would repel external threats. They may have been right. It may have taken the volcanic eruption on Thera, just north of Crete, to weaken the Minoans sufficiently for the newly emerging Mycenaean culture to overtake them. Yet recent evidence about the date of the eruption casts doubt on its contribution to the fall of Minoan civilization. Though it is evident that the Mycenaeans eventually came to control Knossos, how this transition occurred remains a subject for debate.