Our research is funded by:

Allometry: The Big Picture

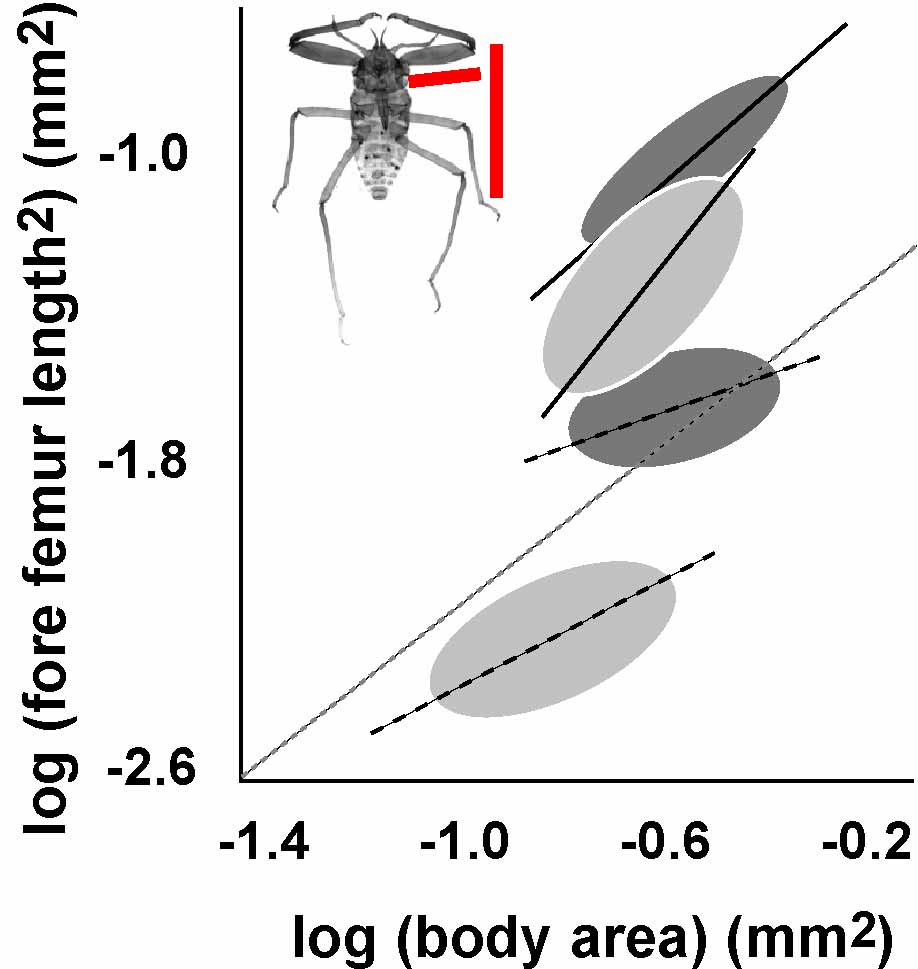

Biological diversity is dominated by variation in shape. This is perhaps no more apparent than in one of the most successful metazoan taxa, the insects. From a very simple body plan (head, thorax, abdomen, a pair of antenna, two pairs of wings and three pairs of legs) comes myriad forms, from bees to beetles, and fleas to flies. Much of this diversity is a result of variation in the relative, rather than the absolute, size of the insect body parts. This variation can be illustrated as a plot of the relative size of two structures among members of a population of animals (Figure 1). This is called a static allometry. When we think about variation in shape, we are often thinking about variation in static allometry (even though we might not realize it!).

Figure 1: Diversity of slopes and intercepts of static allometries among social aphids. Ellipses represent the allometric relationship between fore femur length and body size (red lines on inset image) for two aphids species (light and dark gray). The lines through the ellipses show the mean allometry for the worker caste (dashed line) and soldier caste (heavy line). Dashed gray line is isometry or a 1:1 scaling relationship.

Despite the evolutionary importance of

allometric variation we know almost nothing about the

developmental processes that regulate static allometry.

Consequently, we have very little idea of the types of

genes and developmental pathways that have evolved to

generate variation in allometric relationships. The long

term goal of our research is to understand the

developmental mechanisms that control static allometry in

animals and how it evolves.

Most of our current work focuses on understanding the different aspects of development that control static allometry, using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as our model organism. We have also been interested in how allometric variation among aphids affects their behavior and ecology. Below are some of the projects being conducted in our laboratory.

What controls male genital size (in flies!)?

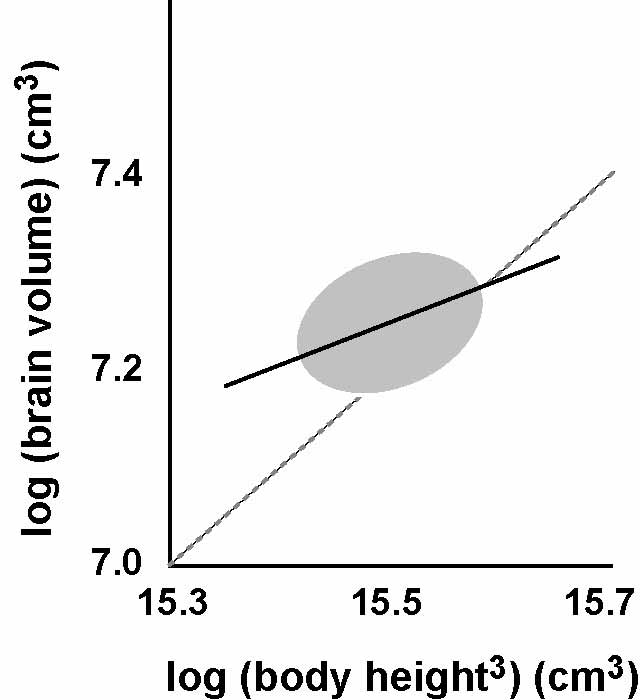

One fascinating aspect of size

regulation is that variation in body size within a species is

not necessarily accompanied by similar variation in the size

of individual organs. For example, among humans, smaller

individuals tend to have correspondingly smaller arms and

legs, lungs and livers. However, the same is not true for

brain size. Brain size tends to be roughly constant across a

range of body sizes in humans, a condition called hypoallometry.

Consequently, smaller humans have proportionally larger brains

(relative to body size) than larger humans.

Figure 2: The relationship between brain and body size in humans. Dashed gray line is isometry or a 1:1 scaling relationship. Data from Koh et al. Neuroreport 16, 2029-32.

There are probably good reasons why brain size varies less than body size in humans - brains are important organs, and development has likely evolved to ensure that conditions that result in a reduction in adult size (for example malnutrition during childhood) retard the growth of the body more than the growth of the brain. However, we have no idea how this is achieved.

In fruit flies, it is not the brain that is hypoallometric to body size, but the male genitals. Consequently smaller male flies tend to have proportionally larger genitals than larger male flies. Over the past few years we have sought to understand the developmental mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon. Early work suggests that differences in the way the insulin-signaling pathway regulates the growth of the genitals compared to other organs is key. Thus the insulin-signaling pathway, which plays a major roles in longevity, diabetes, and the regulation of cell, organ and body size, may be centrally involved in regulating allometry.

Stillwell, R.C., Shingleton, A.W, Dworkin, I., Frankino, W.A. 2014. Tipping the scales: Evolution of the allometric slope independent of average trait size. In revision.Shingleton, A.W., Frankino, W.A. 2013. New perspectives on the evolution of exaggerated traits. BioEssay, 35, 100-107

Shingleton, A.W., Tang, H.Y. 2012. Plastic flies: The regulation and evolution of trait variability in Drosophila. Fly, 6, 1-3

Tang, H., Smith-Caldas, M.S.R., Driscoll, M.V., Salhadar, S. & Shingleton, A.W. 2011. FOXO regulates organ-specific phenotypic plasticity in Drosophila. PLoS Genetics, 7, e1002373

Shingleton, A.W., Estep, C.M., Driscoll, M.V., Dworkin, I. 2009. Many ways to be small: Different environmental regulators of size generate different scaling relationships in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the Royal Society, London. Series B. 276, 2625-2633

Frankino, W.A., Emlen, D.J., Shingleton, A.W., 2009. Experimental approaches to studying the evolution of morphological allometries: The shape of things to come. in "Experimental Evolution" (T. Garland & M.R. Rose, Eds), University of California Press, Berkley. In press.

Shingleton, A.W. & Bates, P.W. 2008. Developmental model of static allometry in holometabolous insects. Proceedings of the Royal Society, London. Series B. 275, 1875-1885

Shingleton, A.W., Frankino, W.A., Flatt, T. Nijhout, H.F. & Emlen, D.J. 2007. Size and Shape: The regulation of static allometry in insects, BioEssays, 29 (6), 536-548

Shingleton, A.W., Das, J., Vinicius, L. & Stern, D.L. 2005. The temporal requirements for insulin signaling during development in Drosophila, PLoS Biology, 3 (9)

What controls body size?

An important aspect of the control of allometry is the

control of body size. In holometabolous insects (insects

that form pupae), final body size is regulated by the point in

development when a larva decides to stop growing and begin to

pupate. This decision is made when the larvae reaches a

particular size, called the critical

size. We are interested in how an insect knows when

it has reached critical size. Early research suggested that

damage to the developing organs in a fly (called imaginal

discs) can delay development. This suggests that the imaginal

discs may need to be at a certain size for a fly to reach

critical size and initiate metamorphosis. We have been using

various physical and genetic methods to alter the growth of

imaginal discs and see how this affects critical size. Our

data indicate that the imaginal discs do indeed help regulate

critical size and the timing of metamorphosis. Even more

excitingly, we have discovered that slowing the growth of one

imaginal disc slows the growth of all other organs in the

body. This suggests that body and organ size is controlled by

a complex set of signals by which growing organs 'talk' to one

another. On going work in the lab is directed to identifying

the nature of these signals.

Mirth, C.K., Tang, H., Makohon-Moore, S., Salhadar, S., Gokhale, R.H., Riddiford, L.M., Shingleton, A.W., 2014. Juvenile hormone regulates body size and perturbs insulin-signaling in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313058111

Callier, V., Shingleton, A.W., Brent, C.S., Ghosh, S.M., Kim, J., Harrison, J.F., 2013. The role of reduced oxygen in the developmental physiology of growth and metamorphosis initiation in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 216, 4334-4340.

Parker, N.F. & Shingleton, A.W. 2011. The coordination of growth among Drosophila organs in response to localized growth perturbation. Developmental Biology, 357, 318-325.

Shingleton, A.W. 2010. The regulation of organ size in Drosophila: Physiology, plasticity, patterning and physical force. Organogenesis. 6, 1-12

Stieper, B.C., Driscoll, M.V. & Shingleton, A.W. 2008. Imaginal discs regulate critical size for metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental Biology. 321, 18-26

Shingleton, A.W. 2005. Body-size regulation: Combining genetics and physiology. Current Biology, 15 (20), R-825-R827.

The evolutionary implications of changes in allometry

Allometric variation clearly underlies much of the

morphological diversity we see around us. Nevertheless, how

does an animal's allometry affect its fitness, and how does

this influence the evolution of its allometry? We have been

studying this question in the aphids. Aphids are small bugs

that parasitize plants. They feed on the plants phloem, which

is high in sugars but low in protein. Consequently, to get

enough protein to grow, the aphids need to ingest a huge

amount of phloem, and get rid of a huge amount of excess

sugar. They do this by producing honeydew, droplets of sugar

water, which the aphids expel onto anything lying beneath

their host plant (ever wondered why you car gets covered in a

sticky goo when you park it under a tree in spring?). Ants

love honeydew, and so in many instances have evolved a

symbiotic relationship with aphid; the aphid produces

honeydew, while that ant protects the aphid from predators.

All aphids produce honeydew, but not all aphids are tended by

ants. We have been studying the factors that influence the

relationship between ants and aphids, and find that allometry

plays a very important role....

Shingleton, A.W. 2011. The regulation and evolution of growth and body size. in "Mechanisms of Life History Evolution" (T. Flatt & A. Heyland, Eds), OUP.

Frankino, W.A., Emlen, D.J. & Shingleton, A.W. 2009. Experimental approaches to studying the evolution of morphological allometries: The shape of things to come. in "Experimental Evolution" (T. Garland & M.R. Rose, Eds), University of California Press, Berkley.

Shingleton, A.W., Stern, D.L. & Foster, W.A. 2005. The origin of a mutualism: A morphological trait promoting the evolution of ant-aphid mutualisms. Evolution, 59 (4), 921-926.

Shingleton, A.W. & Stern, D.L. 2003. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for multiple gains or losses of ant mutualism within the aphid genus Chaitophorus. Molecular phylogenetics and Evolution, 26, 26-35.

Shingleton, A.W. & Foster, W.A. 2001. Behaviour, morphology and the division of labour in two soldier-producing aphids. Animal Behaviour, 62. 671-675.